Norman Brannon: The Shape of Punk Newsletters to Come

Plus, my early days with The Only Band Ever

VANCOUVER — The first hardcore band I ever gave two shits about hails from the tiny border town of St. Catherine’s, ON. Two decades after I first discovered Alexisonfire, the band and its members are more or less mainstays of Canadian culture, contributing as much to the national identity as the Tim Horton’s double-double or the Lululemon scuba hoodie.

While punk broke for me in 2002, with the release of Nirvana’s Greatest Hits, my future with the genre was sealed the first time I saw the video for “Pulmonary Archery” on MuchMusic. The bare bones production features the band performing in a house that may or may not be haunted. With their colourful t-shirts and shaggy hair, I couldn’t help but feel a kinship to these quirked up white boys. They were more like me than Kurt Cobain. And yet here they were, thrashing away on national TV. It was an exciting prospect, one that helped me realize punk wasn’t just some dead genre for depressed pop stars. It was alive and kicking.

To this day, AOF remains popular in Canada and almost nowhere else. I can only speculate as to why, but I suspect it may be because the band traded in two quintessentially Canadian traits: comedy and approachable politeness. The songs contained the necessary angst and distortion, but the band subverted the self-seriousness that I later associated with other acts in the genre. Consider their videos for “Water Wings (And Other Pool Side Fashion Faux Pas)” or “‘Hey, It's Your Funeral Mama.’” This wasn’t Black Flag or Fugazi. This was just five bros having a good fuckin’ time.

While I wasn’t there to read Norman Brannon’s Anti-Matter during its original run as a zine in the early 90s, his Substack of the same name elicits a sensation similar to my early days with The Only Band Ever. His personal essays on punk and hardcore, and interviews with scene legends, excite me to no end, often zeroing in on exactly what makes this music and scene so special.

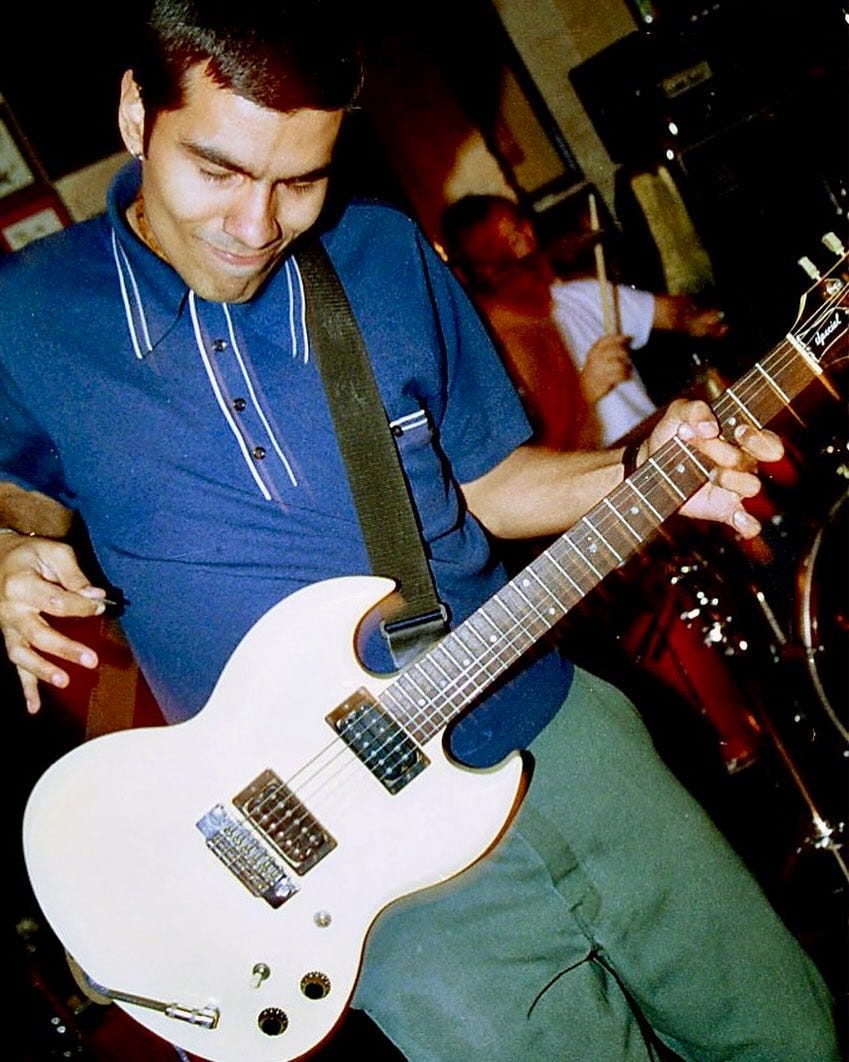

With nearly four decades of experience listening to and playing in hardcore bands (Texas Is The Reason, New End Original, and Thursday, to name a few), Norman has what every writer dreams of: a wealth of lived experience.

Our conversation, which has been edited and condensed for clarity, captured this perspective perfectly, with the publisher reflecting on his early days in New York, embracing your beat, and breaking down his process (among other things).

And so, without further ado.

Get fighted.

NB: Am I present?

ES: You are present. How’s it going?

NB: Alright. I just published a newsletter this morning, so I’m doing that weird thing where you wonder how people are reacting, and what they’re saying.

ES: “What are people saying?” is a much better question than “What common words did I misspell?” which is what I normally worry about. It’s very concerning, especially given that you can’t edit the email once it’s out the door.

NB: That’s funny you say that. My partner only goes in to work two days a week – Tuesday and Thursday – which is when I publish. During his commute, he’ll read the newsletter and send me feedback. “Oh, you’ve got a typo here.” Like, goddammit. Laughs.

ES: I feel so seen right now. I call my fiancée the brains of the operation because when I started, I had so many fucking spelling mistakes. She would highlight them and send them to me. It was so embarrassing. Now, nothing publishes without passing her desk first.

NB: I will say that doing Anti-Matter is more work than I initially bargained for.

ES: Really?

NB: Yes, but I don’t hate that. A lot of the work comes because I want to make something that I’m proud of. That’s a recurring theme with a lot of the stuff that I’ve done. I don’t think I’m the most prolific person, but Anti-Matter forces me to be. It’s a challenge, but I’m into it.

ES: I wasn’t around for Anti-Matter 1.0, but from the outside, you certainly seem prolific. I also love how you use your Tuesday dispatch to preview what’s coming on Thursday, and I’d love to hear more about your strategy.

NB: At the beginning of 2023, Anti-Matter wasn’t a thing. It wasn’t even a germ in my mind. The only thing I knew in those early months was that it was the 30th anniversary of the zine’s first issue, and that that was something worth celebrating. I got in touch with Jordan Cooper at Revelation Records at one point because he was talking about re-pressing the Anti-Matter book. I told him to wait because I loved the anniversary idea and I thought there needed to be a proper 2nd edition with added text. For example, when the Anti-Matter fanzine died, I started doing a column for Punk Planet that was also called Anti-Matter. That ran for several years. I was like, “We need to publish all of these columns.” It’s part of the Anti-Matter story to me.

"There’s something very special about focusing on one thing and becoming an expert on it."

As I was thinking about all of this, it occurred to me that there was a bit of a newsletter format there; that the Tuesday essays could be like the Punk Planet columns, and the Thursday interviews could be like what I did for the original fanzine. I’d been subscribing to newsletters, and I was interested in the idea that email had lost its meaning. Unless it’s for work, nobody sends each other emails anymore, nobody calls each other anymore. We do everything over text messages. That’s the modern condition. It felt interesting to me to work on something where people invited you into their inbox. That seems very personal. I like the idea that people would open up their inbox to me, as opposed to bookmarking a website, which feels impersonal and random.

ES: Would you say Anti-Matter is a document of punk and hardcore? Or is it a document of your life in punk and hardcore?

NB: It’s definitely me and my life. I have a lot of problems with history, and the idea of documenting history, because it often privileges a certain group of voices over others, or erases some groups… When I started the newsletter, I was really careful to think about what I was doing. Part of me thought “Is my voice necessary right now?” In the end I decided that it was. Being a 40-something queer person of colour, who has seen most of four decades worth of hardcore music, and contributed to at least three of them, I think I have a unique point of view, a unique perspective, and a unique way of telling stories. I think that means something. I never want it to feel like I’m telling anyone “How it is” because I don’t feel like that’s a real thing. I think that I can only tell you what I experienced and how I felt, and how I feel in the present tense.

ES: I think you do a good job delineating and making it clear that you are not approaching it from a historical perspective. It’s almost like gonzo journalism in a way.

NB: I used to teach at Brooklyn College and one of the courses I oversaw was for the linguistics department. It’s been a while since I taught it… But I was talking about oral culture and pre-writing culture and how stories were told before the invention of writing. At that time, stories were told in a way that had to be remembered because they had to be passed down. That’s where we get things like mnemonic devices or recurring words. The Bible has a lot of them. Like, “And thus! This thing happened” or “And thus! That thing happened.” All these ways of remembering your stories, and your codes and traditions and passing them down.

I tend to love the idea of storytelling as a way of transmitting history. I think hardcore has a lot of amazing storytellers. A lot of these people from the 80s in New York, at least, were, to me, incredible storytellers. This week, I interviewed Civ from Gorilla Biscuits, and I think he’s one of the most underrated storytellers New York hardcore has ever seen. Not only are his stories interesting and entertaining, but they’re instructive. We learned something about our culture in these stories. I’m not handing down rules the way we once did, but there are ways of being in hardcore that can be transmitted using stories, and I think that’s the tradition that I’m in.

ES: You’re very upfront about your early days and the fact that you didn’t finish high school. And yet you’re a pretty heady, well-educated guy. How did you learn so much? Are you just reading a lot?

NB: My decision to drop out had nothing to do with academics, it was purely social. I grew up in Queens, but in late junior high or early high school, my family moved to Long Island.

Long Island in the 80s, or at least Massapequa, where we lived, was traumatic for me, mostly because in 1988 it was 100% white. I walked into that school and was essentially called the N-word, or “wet back,” or “spic.” Just constantly unwelcome. And that never changed over time. My only way out of it was, on weekends, going back into the city and going to shows or buying records, buying fanzines. That was my social way out. But there was a point when I turned 16 that I felt “I can’t do this anymore. I’m tired of living on Long Island, I’m tired of living with these people.”

School honestly wasn’t challenging either. I wasn’t happy there. I remember being in class and asking my teacher a question, and they responded “Well, that’s not on the test.” And I thought, “I’m not asking because it’s on the test, I’m asking because I’m curious.” I would spend my lunch periods in the library. That was what I wanted to do: to learn about the things I wanted to learn about and read about the things I wanted to read about. And I think I took that attitude with me when I dropped out. Books were a way for me to learn about the world, and writing was the same. I very much think of myself in the spirit of Michel de Montaigne. I’m trying to figure something out, and it will become clear to me when I finish this piece. Laughs.

ES: I feel the same way. Right now we’re seeing this big pivot to video, whether it’s podcasts or TikTok or whatever, and I wonder how you feel about that as a “creator”? Like, are we just banging our heads against the wall by choosing to trade in the written word?

NB: I mean, it’s a different art, right? I’ve never really been much of a visual person in that way… I don’t go to the movies. I like TV, but as a way to palette cleanse. There’s something about words to me that is more open to my imagination. I enjoy reading things that open my imagination and writing things that I think may open up other people’s imaginations.

There are so many aspects to writing that make me happy. I love the feeling when you’re reading something you wrote out loud and it sort of dances on your tongue a little bit. Where you get the cadence just right. It’s like songwriting in a way. Sometimes you write a sentence and it has too many syllables. The cadence is wrong. I need to fix it. The majority of readers won’t even register something like that, but I know, subconsciously, there’s something there that makes them feel good. That’s the magic I’m more interested in.

ES: What’s the higher high: writing a really good song or writing a really good newsletter?

NB: Laughs. Honestly, I think they’re the same. I just love that feeling when you finish something and you know it’s good. So often you finish things and want a second opinion, or feel unconfident about it. And that’s a terrible feeling. I’ve had situations as a freelance writer where I’ve hit the deadline and the piece just has to go. And it sucks. But the feeling of elation when you do something good is pretty even, across the board.

ES: What is your newsletter diet at the moment?

NB: It’s interesting because one of the reasons I started Anti-Matter as a newsletter was that I felt like there wasn’t anyone doing a super consistent newsletter in music, or at least the music I travel in. Substack’s number one music newsletter right now is Ted Gioia — he’s very academic, very astute, and smart. He writes about a lot of stuff, but I don’t know what his beat is. It’s very encyclopedic. Some days he writes about the industry, some days he writes about jazz. It’s interesting, but ultimately I unsubscribed because I don’t know what it’s about.

I look at something like The Status Quo, which is a political newsletter… I like the way he parses what’s happening in the world. It makes me feel more informed and it doesn’t make me feel angry, which is rare in the political space.

ES: I’ve struggled with that. My newsletter was so unfocused when I started and I sort of always want to rebel against the idea of focus; I sometimes think everything is too focused now, so it’s interesting to hear that a more focused product keeps you more interested.

NB: I used to also rebel against focus on some level, so I get it. The first issue of Anti-Matter featured Swervedriver. Like, what? Laughs. I love Swervedriver, I still stan Swervedriver, but in retrospect, I do wish I kept it more focused.

I remember being a freelance writer in the late 90s and writing for Alternative Press or Vibe, and feeling resentful that people were coming to me to write about punk, that punk was my beat. Like, “I know so much about so many other types of music. I could write about anything! I just want to tell stories.” But I started to embrace it. There’s something very special about focusing on one thing and becoming an expert on it. Thinking about every angle of this one thing, and being able to present stories about things that live inside this universe or live on the outskirts of it, that’s unique because you know so much about it.

I think people rebel against beats because they don’t want to limit themselves. But Anti-Matter has shown me that there are no limits. I just published my 27th essay about hardcore and I’m still coming up with new ideas... Every week I wonder “Is this the week that I run out?” But I keep remembering things I experienced. That’s what focusing and zeroing in on a beat can do. It brings up topics that you didn’t even realize were topics; things that you want to preserve in some way.

ES: At the same time, you’re still an active member of the community, you’re touring with Thursday. How has life on the road changed for you since you were touring in the 90s? Or has it?

NB: The nuts and bolts of touring are the same. The only thing that changes is the environment. So, are you touring in a van or a bus? Are you in a situation with people who care about you, or who don’t care about you? I’ve done it all… The mechanics that I’ve struggled with, across those scenarios, is that you’re only working two hours a day — but you feel tethered to those two hours. It paralyzes you from accomplishing almost anything else.

Last year, when I was touring with Anti-Matter, was a really interesting struggle, because the discipline I had to have to keep publishing at the rate that I do is something that I’ve never been able to accomplish on tour before. And I can’t lie it was hard as fuck. There were nights when I’d get off stage and have to write all night. But it was also the first time where I felt like I accomplished anything on tour besides playing shows. It created a new paradigm for me and proved other things are possible on tour.

ES: In a situation like that, are you grabbing your laptop and trying to generate an idea on the spot? Or do you know what you want to talk about and just need to churn it out before your self-imposed deadline?

NB: I try, and often fail, to bank as many interviews as I can ahead of time so that I have the raw material. Then I start transcribing.

As I’m transcribing I’m always looking for the two quotes. One to use on Instagram to go with the interview, and the other that will help springboard the essay. And that’s gotten harder over time because most people tend to say similar versions of the same thing. I’m always looking for that unique piece of interview that gives me a spark. Once I have that piece… I’ll take an entire day and start spit-balling directions or thesis statements, getting on the phone with friends, and talking it through. And of course I’ll have a million left turns once I start writing, until I figure out “This is what I’m trying to say!” When that becomes clear, the writing is a lot faster.

One benefit of touring is that there are tons of people for me to talk to and spitball with… The downside is that privacy is at a premium. I’m constantly trying to find a place to work, a place where I don’t feel like I’m being rude. Luckily, on this last tour, the guys in Thursday are very understanding and supportive. They essentially gave me the back lounge of the bus to use as a de facto office for almost the whole run.

ES: Between you and Geoff [Rickly] that band is turning into the punk-rock Inklings.

BN: To his credit, Geoff does a lot of his writing in his bunk on an iPad, which is not something I can do. I need the generic writer creature comforts; a desk, a cup of coffee.

As a kid, I would always ask people in the scene “What fucked you up to be here?” And they always had an answer! No one came not fucked up.

ES: Do you have any broader ambitions for Anti-Matter?

NB: I knew when I started, that this wasn’t the end all be all. I’ve always seen Anti-Matter as its own universe. That encompasses the ideas and music I like to promote, but also the fact that in the 90s this was a zine, a column, a compilation album, a series of shows in New York. It was whatever I wanted it to be. And when I started publishing again… I knew I could maybe use it to springboard other ideas if enough people wanted it.

The irony, given what we’ve been talking about, is that one of my ideas is a docu-series about hardcore from an Anti-Matter perspective. I always thought that would be interesting. I’ve been critical of the punk documentaries and punk docu-series that have existed so far because I feel like they become a platform for people to convince you how cool they were. I’m not interested in those stories. I’m more interested in questions like “Who were you? What were you feeling? What were you going through at this point in your life?” That’s Anti-Matter’s M.O.

As a kid, I would always ask people in the scene “What fucked you up to be here?” And they always had an answer! No one came not fucked up… I think those stories are also part of the hardcore tradition. I would love to create a space where people could tell those stories, as a way of understanding the thing that we do, and this thing that has survived for four decades.

ES: How did you get so well-adjusted?

NB: I’m not. Laughs. I was talking with my best friend Rob Fish, who sings in the band 108, about hardcore and why, at our age, this is still something that we do. We concluded that the only reason we’re still here is because we’re still fucked up. And I think that’s the point. If anyone tells you that they’re a hardcore kid, but everything’s great, they’re lying to you or they’ll be gone next week.

Norman Brannon is the publisher behind Anti-Matter. He lives in New York City.